author: Mara Krause, 15.08.2025

Quantum mechanics hugely contradicts the classical way of thinking but drastically changed life with its astonishing applications. However, quantum mechanics remains a mystery and interpretations differ wildly. One of the most famous interpretations is the Copenhagen Interpretation. This article examines the Copenhagen interpretation with three pivotal experiments – the double slit, delayed choice and quantum eraser experiment.

What does the Copenhagen Interpretation propose?

The Copenhagen Interpretation proposes that a quantum system is described by its wave-function with probability amplitudes as it has no definite properties but rather exists in multiple states, known as superposition. Measuring the quantum system changes the state and forces a single eigenvalue: the observed reality.

In other words, quantum systems are in superpositions until observation collapses the superpostion into one state. The standard Copenhagen does nor require a conscious mind for the measurement, although some scientists speculate about consciousness-induced collapse.

Macroscopic objects do not show superpositions as they constantly interact with their surrounding environment, causing instantaneous decoherence.

What is the double slit experiment?

The double slit experiment remains the most striking demonstration of quantum mechanics. In 1969 Claus Jönsson realized the first double-slit experiment with electrons.

Electrons are fired individually at a barrier with two narrow slits. Behind the barrier is a detection screen that shows where they land.

Without measurement the screen records an interference pattern, suggesting that each electron passes through both slits simultaneously and interferes with itself, like a wave.

Placing a detector at each slit to see which path the electron takes, the interference pattern vanishes. Instead, a broadened non-interference pattern emerges on the screen, demonstrating the behaviour of classical particles.

How can the double slit results be explained?

According to the Copenhagen Interpretation, the measuremtent form the detector changes the quantum system. Before, the electron passes through the slit in a superposition without having defined properties of wave nor particle, just a wavefunction whose amplitude passes through both slits. Then, the detectors collapse this superposition, giving the electron classical properties, thereby destroying the conditions necessary for interference. At its core, this interpretation solves the paradox by rejecting the idea that quantum particles have definite properties or paths independent of observation.

Richard Feynman announced in his famous Feynman lectures that the double slit experiment is the ultimate experiment for quantum mechanics as it involves wave-particle duality, particle trajectories, collapse of the wave function and uncertainty principle. But John Wheeler further developed the double slit experiment to the delayed choice experiment and the quantum eraser experiment.

What is the delayed choice experiment?

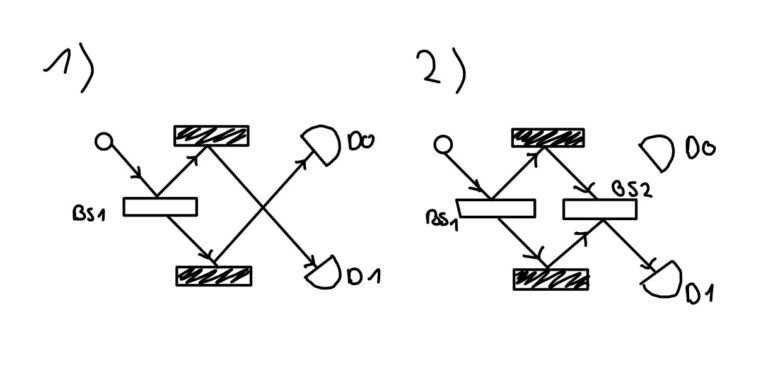

John Wheeler originally proposed the delayed-choice experiment to demonstrate a paradox regarding retrocausality due to quantum mechanics and wave- or particle-like behavior. It involves a source of single photons, two beam splitter BS1 and BS2, mirrors to redirect, and two detectors D0 and D1. The delayed-choice experiment has two scenarios:

- A single photon is emitted towards a beamsplitter, bringing the photon in a superposition traveling up or down. Either path has a mirror that directs the photon to the detector D0 or D1 depending on the direction. Both detectors will detect it with equal probability. (10)

- The single photon has to pass another beamsplitter after being reflected off the mirror. It has already been in a superposition; hence the paths interfere. In the end, only D1 will detect the photon 100% due to destructive interference at D0. (10)

The assumption at the time was: the first scenario reveals particle-like behaviour without interference, the second scenario reveals wave-like behaviour.

In 1978, Wheeler wondered what happened when a quantum random generator decides randomly whether the second beamsplitter is activated or not (first or second scenario) only after the photon passed the first beamsplitter.

This appears to create a paradox: the decision of the random generator seems to retroactively determine to past of the photon. Future decision of the random generator either reveals a particle- or wave-like behaviour of the photon during the first beamsplitter. Wheeler said himself, „we have a strange inversion of the normal order of time. We, now, by moving the mirror in or out have an unavoidable effect on what we have a right to say about the already past history of that photon.” (…) “Thus one decides whether the photon shall have come by one route as particle or by both routes as an interfering wave after it has already done its travel”(11)

How can the delayed-choice experiment be explained?

The Copenhagen interpretation argues the photon neither was a particle nor a wave at BS!, it was in a superposition state. The choice to activate or not BS2 simply determines which observable is measured at the end. Not retrocausality influence is required.

What is the quantum eraser experiment?

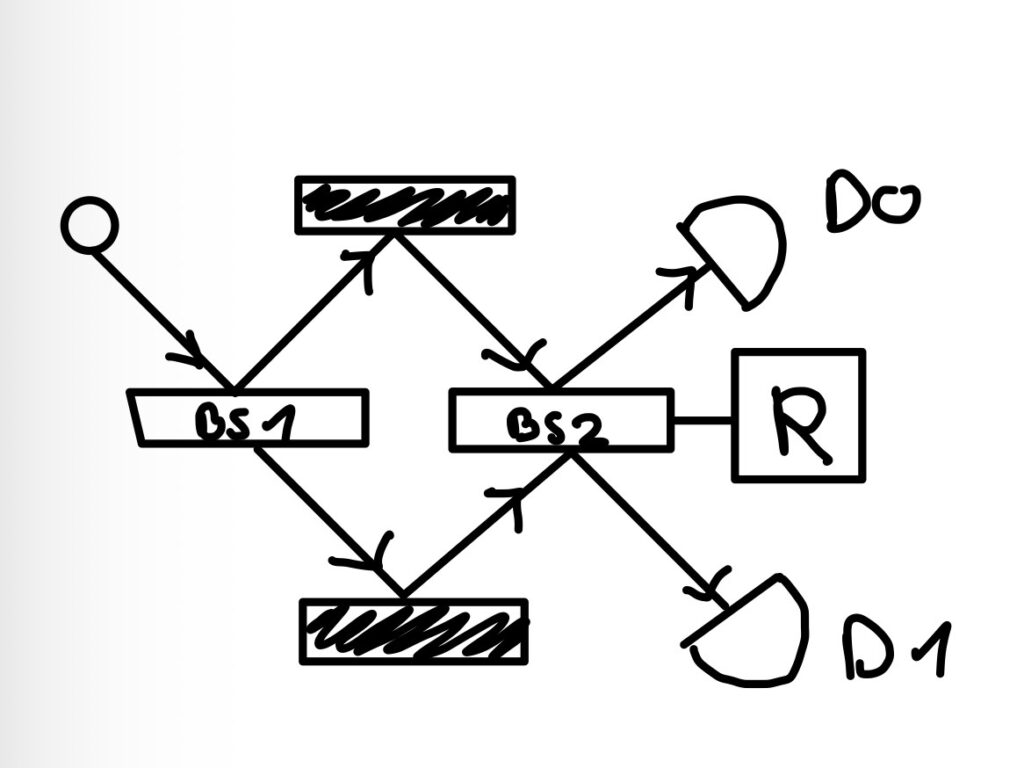

The quantum eraser experiment also explores the paradox of retrocausality, exploring the behaviour of superpositions. Entanglement plays a key role: entangled particles have linked quantum properties. Hence, one can determine the state of a particle by measuring its entangled partner.

The setup of the experiment involves a crystal that entangles two photons. One photon (signal photon) travels through a double slit and is detects by D0. According to its nature, it shows an interference pattern or not, although the raw data never shows clean interference, only after selection an correlation analysis.

The other entangled photon (idler photon) is routed through a beam splitter to detectors D1-D4. D1 and D2 erase which-part information, hence destroying information about the signal photon. D3 and D4 reveal which-path information, hence the behaviour of the signal photon. D0 detects the signal photon before the idler photon is detected by one of the detectors.

Repeating this experiment shows that signal photons whose entangled partners are detected by D1 or D2 create an interference pattern in coincidence with D0 after sorting into subsensembles. Meanwhile, signal photons whose entangled partners are detected by D3 or D4 don‘t create this interference pattern. The paradox arises as the signal photon reaches D0 before the idler photon can „determine“ its behaviour. „So, the question is: how is it possible for a signal photon to make a choice depending on what will happen to its idler twin later?“ (12)

How can the quantum eraser experiment be explained?

The Copenhagen interpretation approaches this paradox as following: entangled photons have to be treated like a single quantum system, not as separate ones. Marijn Waaijer and Jan van Neerven conclude: „In fact, questions such as whether the photon “was” a wave or particle at the various stages of the experiment – the centrepiece in arguments purporting to demonstrate retro-causation – are completely meaningless from an operational point of view and can only lead to pseudo-problems.„ (10)

A modern „Copenhagenish “interpretation argues that measurement does not actually collapse the objective superposition but rather shows a subjective reality. The photon stays in a superposition the whole time, we just perceive a subjective reality. Measurement collapse is an illusion.

The temporal paradox of the experiments may reflect our classical assumptions of time. Relativity shows that time „stops“ for photons as they travel with the speed of light. The theory of relativity explains that time is measured relatively to the light-speed, and it slows down the closer one gets to light-speed. Particles with light-speed should not experience time which challenges the paradox of „future measurements influence past states“.

What are complications with the Copenhagen Interpretation?

The most challenging complication might be the measurement problem. How and when does the superposition collapse into a definite state? The problem is the unspecification when quantum behaviour end and classical behaviour begins. The Copenhagen Interpretation lacks an explanation form probabilistic Schrödinger equation to an observed state.

In a paper form 2023 Kirshnan, still critical, offers the point of view that measurements do not collapse the superposition. They merely give one perspective on reality and not the full reality. Properties of a quantum system are only created via measurement.

A recent analysis notes that „to date, there has been no precise definition of a Copenhagneish interpretation, which makes it difficult to understand the common principles underlying them.“ (8). Moreover, the direction of the outcome after measurment appears to be completely random. This raises question about the nature of this randomness. Does „random“ mean completely undetermined, or merely unpredictable due to hidden parameters we cannot access?

What might be an alternative interpretation?

Another interpretation of quantum mechanics is the Many-Worlds interpretation. It suggests that each time a wave-function collapses, the universe splits. While Copenhagen interpretation limits reality to observation, Many-Worlds states that all possibilities exist and we are just stuck in one of them.

Kabine compares in a paper form 2024 the Copenhagen and Many-worlds interpretation (MWI) and concludes that „ While MWI eliminates the need for wave function collapse and hence is attractive in its simplicity and elegance in maintaining the form of the wave function, it introduces the ontologically extravagant concept of an infinite number of unobservable universes. This raises issues with the criterion of simplicity as it complicates the ontological framework without offering additional predictive power or empirical benefits over the Copenhagen interpretation.“

If one adopts the consciousness-collapse view of the Copenhagen, is it proof for the non-existence of a god-like omnipotent creature? Quantum systems could not remain in a superposition with God, an observer. Current experiments on quantum computers show the difficulty to maintain systems in superpositions as even slight gravitational waves can collapse the superposition by leaking information to the outside world. An omnipotent observer would collapse all superpositions. Normally, non-existence, or the negative, cannot be proven. Although no one has seen unicorns so far, there is a small probability of their existence. But a logical result form superpositions is that no all-observing creature can exist. However, this view is not part of the orthodox Copenhagen and lacks support, hence cannot be used as a serious argument.

References

1) J. Gribbin, In Search of Schrödinger’s Cat: Quantum Physics and Reality, Black Swan, London (1984).

2) IN2P3/CNRS, “Neutrino History,” https://neutrino-history.in2p3.fr

3) A. Ney and D. Z. Albert (eds.), “Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/qm-copenhagen/ (accessed June 30, 2025).

4) ThisScience1, “The Copenhagen Interpretation Is Wrong — Here’s Why,” Medium, https://medium.com/@thisscience1/the-copenhagen-interpretation-is-wrong-heres-why-de526a8a3471 (accessed July 1, 2025).

5) W. Heisenberg, “The Development of the Interpretation of the Quantum Theory,” in Niels Bohr and the Development of Physics, McGraw–Hill, New York (1955). Available at https://www.astrophys-neunhof.de/serv/Heisenberg1955.pdf (accessed June 27, 2025).

6) R. Shankar, Fundamentals of Quantum Mechanics, 3rd ed., Wiley-VCH, Chapter 1 (2012). Sample chapter available at https://application.wiley-vch.de/books/sample/3527347925_c01.pdf (accessed July 2, 2025).

7) Number Analytics, “Philosophical Analysis of the Copenhagen Interpretation,” https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/philosophical-analysis-copenhagen-interpretation (accessed June 30, 2025).

8) D. Schmid, Y. Ying, and M. S. Leifer, “Copenhagenish Interpretations of Quantum Mechanics,” arXiv:2506.00112v2 (2025).

9) “Measurement and Probability,” in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2025 edition, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2025/entries/qm-copenhagen/#MeasProb (accessed June 30, 2025).

10) A. Author(s), “Title,” arXiv:2307.14687 (2023). https://arxiv.org/pdf/2307.14687

11) X.-S. Ma, J. Kofler, and A. Zeilinger, “Delayed-Choice Gedanken Experiments and Their Realizations,” Reviews of Modern Physics 88, 015005 (2016).

12) H. Zwirn, “Delayed Choice, Complementarity, Entanglement and Measurement,” arXiv:1607.02364 (2016).

13) G. V. Krishnan, “How Bohr’s Copenhagen Interpretation Is Realist and Solves the Measurement Problem,” arXiv:2308.00814 (2023).

14) Quantum Zeitgeist, “Scientists Self-Test Quantum States with Just Two Measurements,” Quantum Zeitgeist (August 2024), https://quantumzeitgeist.com/scientists-self-test-quantum-states-with-just-2-measurements/ (accessed July 1, 2025).